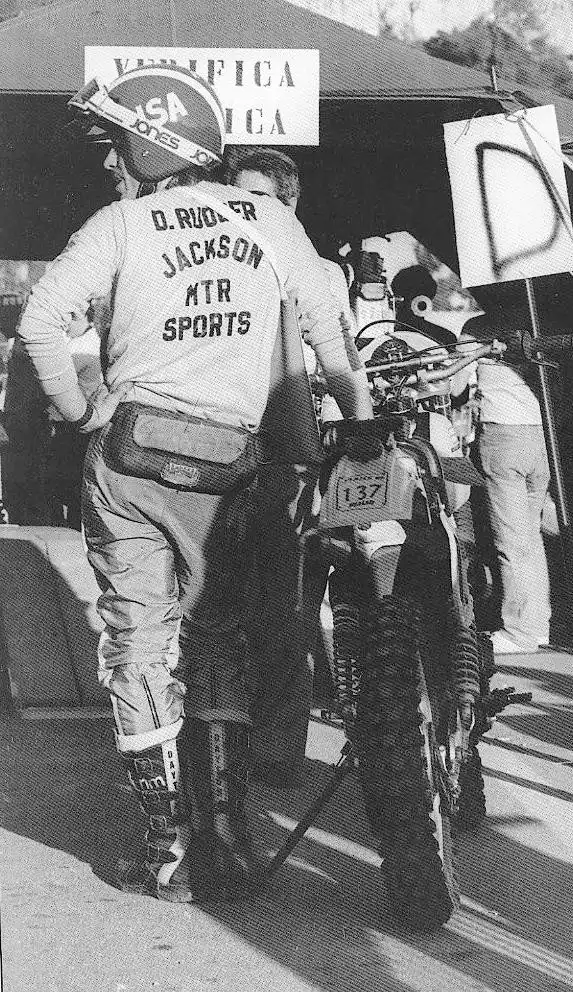

Dwight Rudder

BEEN THERE, DONE THAT

by Ted Guthrie

Originally printed in the 2009 issue #43of Still….Keeping Track

Alabama native Dwight Rudder is “the real deal”. He’s been on numerous factory enduro teams, earned medals in multiple ISDT competitions, has been an “A” enduro rider for decades, and those are just a few of his motorcycling accomplishments. There is in fact a lot more to this quiet, polite fellow with the southern drawl, besides.

Dwight was raised in Greensboro, Alabama, hence the southern accent. However, where his exceptional motorcycle riding skills came from is anyone’s guess. He didn’t come from a motorcycling family, but Dwight’s father did introduce him to the sport at age 9 with the gift of a lawnmower engine-powered minibike. Dad also had a Harley 165 stashed in the barn, which was brought out and coaxed back into operation when Dwight was 12. While Dwight did put some time on the bike, he was initially scared of it. Later came another minibike, but then Dwight graduated to a Suzuki T250 Scrambler. Despite its rough and ready moniker, the Suzuki didn’t turn out to be a very good trail bike. As a result, Dwight traded it for a ’69 Yamaha AT1, aboard which he rode his first enduro in 1971 in Brent, Alabama and his second a few weeks later at the famous “GOBBLER GETTER ENDURO” in Maplesville, Alabama.

Along about this same time, Dwight’s father took him to see the motorcycling film classic, “On Any Sunday”. Although Dwight enjoyed the entire film immensely, it was the segment which featured Malcolm Smith’s performance in the International Six-Day Trial that really excited the young racer. Right then and there Dwight decided that ISDTtype competition was going to be his primary pursuit and Malcolm Smith became his number one hero. So, how did a young man correspond with his hero back in the 1970’s? Why write fan letters, of course. And, being the friendly guy that he is, Malcolm responded with letters of his own, as well as photographs of himself and his motorcycles.

Meanwhile, Dwight had moved on to a Yamaha CT-2 175, followed by a 175 Jackpiner, and then a Penton 125 Six-Day, on which he began competing in 2-Day Qualifiers. At the Ft. Hood, Texas Qualifier, in 1975, Dwight had stopped alongside the trail to fix a problem with his Penton’s throttle cable when none other than Malcolm Smith himself stopped to see if he needed any assistance. Dwight already had the cable repaired, but he did however accept Malcolm’s offer for them to ride together. And so it was it was that Dwight found himself riding in the company of his boyhood hero.

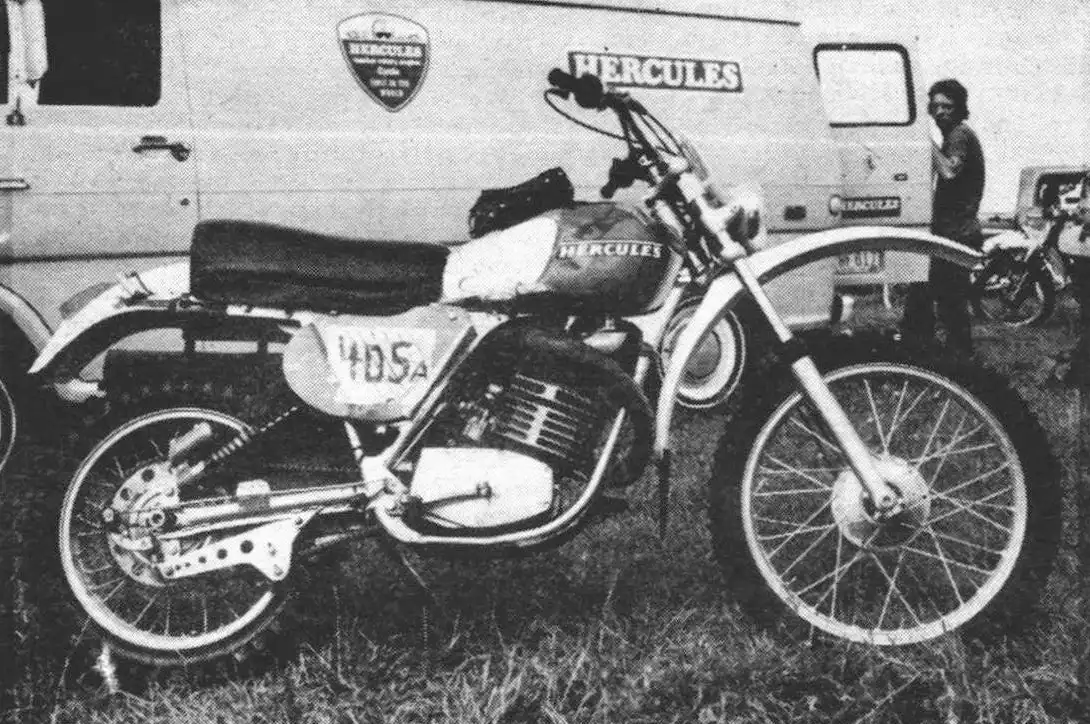

This very special experience came to a premature end though, when Dwight’s 125 Six-Day sheared its shift key. By the time Dwight managed to get in off the course, it was late and nearly everyone else was packed up and gone. Among those still around however was Malcolm, who promptly came over to talk to Dwight. Malcolm complimented the young Penton rider on his fine ride earlier in the day and when Dwight introduced himself, Malcolm’s eyes went wide and he took a step back. “There used to be a kid by that name that wrote fan letters to me!”, he said, partly surprised and more than a little impressed as Dwight turned a very embarrassed red. Dwight recalls that he will never forget this initial meeting with Malcolm Smith. The entire experience, from riding with his hero, to Malcolm actually remembering him from the fan letters, absolutely galvanized Dwight’s opinion of Malcolm Smith as a top rider and as a wonderful person and they remain friends to this day. Dwight Rudder rode this prototype 125cc

Dwight continued competing in the Qualifiers, and did quite well. He met the Penton family and the entire Penton team, and was very honored when Dane Leimbach invited him to pit out of the famed Penton Cycleliner. Then, during the offseason, just after moving from Alabama to a new home in Jackson, Mississippi, Dwight was contacted by Doug Wilford, with an offer to ride Hercules motorcycles the following year. Doug had at that time recently taken a position with the Hercules importer and recognized the talent and potential of this young rider.

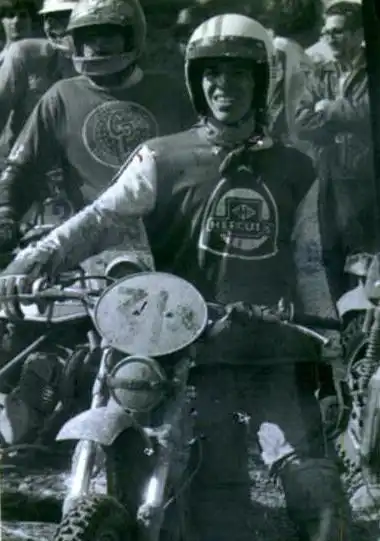

The first time Dwight had any experience at all with the Hercules motorcycles was early September, 1975, when he met with Doug at Tennessee’s Loco Ciento 1-Day Qualifier. There, he rode a prototype 7-speed Hercules 125. Despite drowning the bike out in a creek crossing due to what Dwight determined later to be poorly placed louvers in the airbox opening, Dwight tied for 2nd place in the 125 class with his friend, Teddy Leimbach. Steadily gaining experience through this and other strong rides aboard both six and seven-speed Hercules 125 and 175 models, Dwight remained with the team from 1975 through 1977.

Dwight’s performances during this time qualified him to ride the ISDT in ’76. Unfortunately, he was denied the opportunity by Al Eames, who told Dwight that he didn’t have enough experience. “Rider selection for the ISDT team was not an entirely Democratic process back then”, Dwight comments dryly. Dwight also qualified to ride the ISDT in 1977, but was injured prior to the event. This particular injury was not the result of either a motorcycle riding or racing accident, but rather from another aspect of Dwight’s amazing life experiences.

This goes back to Dwight’s father, who was in the Air Force. Although Mr. Rudder did not serve in the USAF as a pilot, he did earn his pilot’s license while in the service. He then started his own crop dusting service in Alabama and later in Mississippi. Exposed to his father’s experience and influence, Dwight earned his student pilot’s license at age 14, followed by a commercial pilot’s license as soon as it was legal to take the test. And so, it was in one of his father’s crop dusting planes that Dwight suffered injuries which prevented him from participating in the 1977 ISDT. While flying over a particular farm field in Canton, Mississippi, while crop dusting, Dwight saw that the aircraft was going to come too close to some power lines. He managed to avoid the power lines by flying under them, but then could not quite clear the trees on the other side. A large tree ripped one of the plane’s wings entirely off, causing the aircraft to spin three times before crashing into the ground. Dwight suffered a broken collarbone, as well as a concussion so severe that it left him blind for several days. This unfortunate situation did result in one positive however, as it was during his recovery time that Dwight began to date a young lady named Debbie whom he had met some time before. The courtship blossomed and Dwight and Debbie eventually married, the union having lasted now for more than 30 years.

The year after his accident, Dwight was selected to ride on the brand-new Yamaha factory enduro team, along with Dane Leimbach, Carl Cranke, Chris Carter, and Jim Fishback. And, Dwight once again qualified well enough to ride the ISDT. Once again however, he was denied the chance to ride the event, this time by “team politics”, as Dwight puts it. The AMA wanted a SWM rider on the team and told Dwight that they had enough Yamaha riders. (That SWM rider went out on Day 2).

The Yamaha ride lasted only through the 1978 season, as the team was dissolved after just one year. However, Dwight did pick up partial support from Suzuki for 1979, and aboard the yellow bikes rode his first ISDT, held that year in Germany where Dwight earned a silver medal. Riding for Suzuki again in 1980, Dwight missed out on that year’s ISDT due to a dislocated ankle suffered at the Trask Mountain Qualifier.

In 1981, Dwight was convinced by Suzuki to assist in creating and campaigning a one-off concept enduro bike. The machine was based on an RM125 motocrosser, but was fitted with different gearing, altered power characteristics, modified suspension, a lighting coil, enduro lighting, and a larger fuel tank. This motorcycle became the world’s only factory PE125. Dwight qualified on the bike for the ISDT, which was held that year on the Island of Elba, located in the Mediterranean Sea. The Suzuki performed well, and Dwight was well on his way to earning his first gold medal when the bike’s pipe cracked during the final moto. The resulting devastating loss of power dropped Dwight in the field, resulting in a silver medal finish. Surely an outstanding performance regardless, but sadly just short of Dwight’s ultimate goal.

In 1982 Dwight signed on for a support ride with Husqvarna to campaign a 125XC. He qualified once again for the ISDT, held that year in Czechoslovakia, an event which would become known as one of the toughest ever in the history of the Six-Day Trial. In terrible conditions rain, cold, mud, and more rain, over some of the toughest terrain imaginable, all the riders in the event struggled.

Dwight performed well on the little 125 Husky until the third day when he blew out his knee. He continued to ride however, in tremendous pain, and unable to even stand on his right leg. Also, through a combination of the wet and cold conditions, Dwight suffered hypothermia. And yet, through shear determination and by carefully limiting use of his injured knee, Dwight managed to finish the event - one of only 8 Americans to finish, out of 36 that started. He credits part of this accomplishment to, of all sources, riders from the Czech team with whom he had made friends. These competitors, who had dropped out of the event due to mechanical problems, would go out to the really impossible sections of trail and wait for Dwight to come along, then help him through. Such outside assistance was not entirely illegal in this particular ISDT, as even event Course Marshals were involved in assisting riders through certain impassable areas. The conditions were that tough.

For the 1983 season, Dwight decided to switch to competing in the U.S. National Enduro series. He started out riding a private Maico Enduro, but soon decided the bike was not well suited for enduro competition. He then switched to a 250XC Husky, and promptly won the A-class overall in his first National Enduro (Little Harpeth Nat’l Enduro). Dwight went on to finish the season first 250A, Overall A, and 5th overall for the year, then moved up to the AA class. In 1985 he rode a 350 KTM, then in 1986 was selected to ride for Kawasaki’s Team Green, on a KDX200. Dwight enjoyed a number of good rides aboard the KDX that year, including a third place overall in the Jack Pine Enduro.

In 1987, Al Baker offered Dwight a ride on XR250 Hondas. Together with Al, Dwight modified the bikes, increasing displacement to 280cc, along with numerous other modifications and improvements. On one of these XR’s, Dwight rode the ISDT that year in Poland, competing in the 350 class. Riding on Gold time, Dwight crashed hard on the last day. He got up and continued on, but at the next checkpoint noticed oil leaking badly from the bike. An inspection showed that the crash had apparently knocked a hole in one of the sidecases. Working frantically, Dwight was able to clean the case well enough to get some epoxy to at least stem the oil loss. Armed with a couple of extra bottles of oil, Dwight took off down the trail. He had lost much time however, and saw his gold medal slip to a bronze by the finish.

Determined to wring even more power from the XR250 motor for the next year, Dwight punched it out to 300cc and installed a custom built Poweroll stroker crank. Despite Al Baker’s concerns that the motor would never last, Dwight began competing on the bike and found it to be reliable as well as a virtual rocket. Unfortunately, on the eve of that year’s ISDT while putting the bike through final tuning, the engine did blow up. In desperation, and with no time to spare, Dwight and Al took the motor from Al’s personal XR and installed it in Dwight’s bike. While not on par with the power Dwight had built into his own motor, the one from Al’s bike would have to do. Only one problem – Dwight noticed that there were no serial numbers on the cases. Al explained that through all the development work he had done on the motor, the cases were “replacement” parts and so had no factory serial stampings. With nothing to lose, Al produced a set of metal engraving stamps and he and Dwight proceeded to mark the cases with the ID: “OICU812”. And, with this fictional serial number the bike passed tech inspection and Dwight rode it successfully in that year’s ISDT.

For the 1989 season, Dwight duplicated his ’88 XR300, but this time supplemented with a higherperformance cam, supplied by Mega- Cycle. The stroker crank was once again employed as well. Dwight had determined that the ’88 failure was the result of a mechanic failing to re-weld the crank properly, and so felt confident of the reliability of this setup. Besides, the bike was now even more of a rocketship. Dwight reports that the power he got out of the little four-stroke engine was just amazing. And, the bike’s overall performance was vilified by Dwight’s successful ride to a Gold in the German ISDT that year.

For 1990, Dwight went back to Suzuki for a season, riding a DR350. Aboard it, he won the 4 stroke A class in National Enduro competition. Then, for the next few years he returned to riding Honda XR’s – but this time on the booming 600’s. For several years he continued to ride the big Honda four-strokes, regularly winning his class in national competition. Dwight’s final ISDT appearance was in 1994, when he competed once again on a modified XR250 (315cc) Honda, and earned a silver medal. In his 7 ISDT and ISDE competitions, Dwight earned 1 gold, 4 silvers, and 2 bronze medals, finishing every event.

So, with all these experiences under his belt, what is Dwight Rudder up to these days? Well, he still competes occasionally in National Enduros, and consistently places well in the Super Senior Class. He also rides the Senior A class in Southern Enduro Riders Association events. He also collects vintage motorcycles, which presently number “about 70” according to Dwight. Note that all of these bikes are “riders”, and almost all are vintage enduro bikes. Dwight has a couple of older street bikes, including a 1989 Honda GB500 single – well known among collectors for its classic British club-racer styling. And of course several Pentons are part of Dwight’s collection, including at present a Steel-Tanker Bershire, a Steel-Tanker Six-Day, a CMF Six- Day, and a ’73 Jackpiner. His preference in regard to collecting and maintaining his bikes is originality, Dwight reports. He likes the bikes to maintain their original appearance and performance. There are a few exceptions of course, such as his slightly modified 1987 Honda XR200R that he rides in Post- Vintage and modern events, as well as a somewhat “breathed-on”, modern, aircooled, Honda CR230F that he is currently racing in the modern Enduros and in Hare Scrambles. Dwight is also a history buff, participating in Civil War reenactments. And, he maintains his pilot’s license and love of flying as well, having recently owned and flown a replica of a 1916 WWI French Nieuport aircraft.

Dwight has worked for the wholesale motorcycle parts distributor, Parts Unlimited since 1987. Wife Debbie is involved with the motorcycling sport as well, having pitted back in the old days not only for Dwight, but for the Yamaha and later the Suzuki and Husqvarna Enduro Teams. Today, Debbie continues a role she has held for some years as the Secretary/Treasurer of the Southern Enduro Riders Association. “She knows her stuff, too” Dwight says. “Why, over the years many top riders such as Dick Burleson have approached her to ask questions in regard to the association’s rules and regulations.” Debbie tried her hand at enduro competition, but these days is content primarily to zip around to gas stops on her street-licensed Yamaha TTR125.

When asked about stories from the old days, Dwight says that he hardly knows where to start. Some of the stories involve riding and racing of course, but there are also “behind the scenes” recollections. One such story is from the ’82 ISDT in Czechoslovakia. Dwight described how the British team, in a fit of overzealous revelry, hoisted a GORI motorcycle up on top of the entrance awning of the hotel where the English-speaking riders were staying. Responding to the disturbance from this activity, the local police arrived and burst into the hotel room, through which the bike could be accessed. By coincidence, said room was occupied by Jack Penton, who had no idea what was going on and was more than a little concerned about a group of Czech Republic Police storming into his room. However, they merely wanted to haul the little motorcycle through Jack’s window in order to return it to street level and to its rightful owner.

Like all of us, Dwight is feeling some aches and pains these days and injuries from over the years have begun to catch up with him. He has the bad knee, issues with the rotator cuffs in his shoulders, and has had surgery on his back as well as some work done to repair a nerve in his neck. However, you wouldn’t know it by the way the man still rides. And so, look for Dwight at this year’s ISDT Reunion Ride. You’ll never know what bike he may turn out on, but just look for one of the really fast guys, sporting an American ISDT helmet, and who talks with an unmistakable southern twang.